Afterlife

FDG Projects - Fréderic de Goldschmidt Collection, Brussels

Text by Laura Amann

“You just want and want and want. You believe in yourself excessively. You don’t believe in Nature anymore. It’s too isolated from you. You’ve abstracted it. It’s so messy and damaged and sad. Your eyes glaze as you travel life’s highway past all the crushed animals and the Big Gulp cups. You don’t even take pleasure in look- ing at nature photographs these days. Oh, they can be just as pretty as always, but don’t they make you feel increasingly ... anxious? Filled with more trepidation than peace?”

Joy Williams, Ill Nature

Of course they do, because we know only too well, we are on the brink of losing all the extraordinary beauty we can see on those overly photoshopped idyllic images, bursting with supernatural colours and glaring from traveling guides, animal documentaries or the latest national geographic special - the irony. It is precisely these images, which leave the ‘bad stuff’ out, that make us increasingly aware that we are doing too little, too late. Can you feel that? The guilt? The regret? Now would be a good moment to become a little hysteric, at the very least.

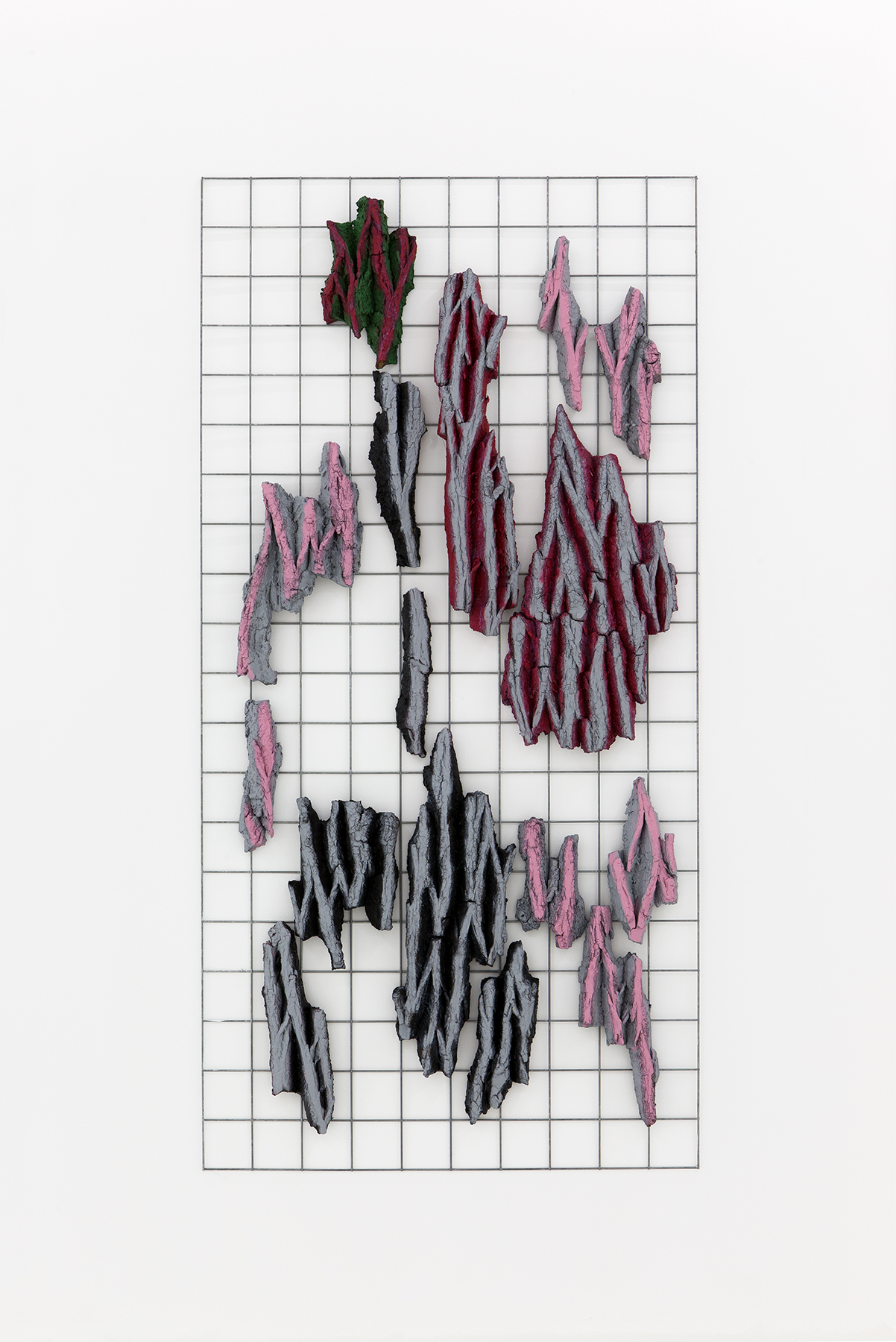

Adam Vačkář ’s exhibition Afterlife shows precisely what is left out in that otherworldly imagery and what could be a future that ultimately is already here. Creating an unlikely arch from Czech surrealism, the only of- ficial surrealist group outside of France and 80’s horror movie make up techniques we are drawn into a space where pollution and toxicity are equally attractive as they are repulsive. A warning sign like a siren’s call. Natural shapes, intuitively collected and assembled are made up into uncanny artificial beauties. These organic objects, often shaped by decade long processes of growth or decay, are alienated through the application of

Joy Williams, Ill Nature

Of course they do, because we know only too well, we are on the brink of losing all the extraordinary beauty we can see on those overly photoshopped idyllic images, bursting with supernatural colours and glaring from traveling guides, animal documentaries or the latest national geographic special - the irony. It is precisely these images, which leave the ‘bad stuff’ out, that make us increasingly aware that we are doing too little, too late. Can you feel that? The guilt? The regret? Now would be a good moment to become a little hysteric, at the very least.

Adam Vačkář ’s exhibition Afterlife shows precisely what is left out in that otherworldly imagery and what could be a future that ultimately is already here. Creating an unlikely arch from Czech surrealism, the only of- ficial surrealist group outside of France and 80’s horror movie make up techniques we are drawn into a space where pollution and toxicity are equally attractive as they are repulsive. A warning sign like a siren’s call. Natural shapes, intuitively collected and assembled are made up into uncanny artificial beauties. These organic objects, often shaped by decade long processes of growth or decay, are alienated through the application of

paint and resin, invoking a surrealist spectre displayed on industrially produced, rigid grids that paradoxically remind us of a more Cartesian approach to reality.

Vačkář ’s distinct combination of organic blob and strict raster are also reminiscent of another surrealist technique that seems strangely close to contemporary post-truth political discourse, namely Dali’s infamous paranoiac-critical method, which suggests a sequence of two consecutive but discrete operations: firstly the synthetic reproduction of the paranoiac’s way of seeing the world in a new light - with its rich harvest of unsuspected correspondences, analogies and patterns and secondly the compression of the these gaseous speculations to a critical point where they achieve the density of fact. But who is actually using this technique - is it the climate change deniers? The teen activists of Fridays for Future? The radical right-wing fear-mongers? Or the hysterical leftist hippies? Or all of us?

Gazing at the mutilated wood logs on the other hand, their hybrid all to human fragile and injured nature, we realize that it is time to leave these dichotomies behind and finally adopt a much more syncretic approach as Stacy Alaimo does in her 2014 publication ‘Bodily Natures’ where she proposes to follow an environmental ethics along the lines of trans-corporeality, meaning that human bodies and non-human natures are open to one another, always constituting each others environment and rendering the idea that we are alone in the universe nothing short of delusional; or very simply put: what we do to the environment, we ultimately do to ourselves.

Text by Laura Amann

Vačkář ’s distinct combination of organic blob and strict raster are also reminiscent of another surrealist technique that seems strangely close to contemporary post-truth political discourse, namely Dali’s infamous paranoiac-critical method, which suggests a sequence of two consecutive but discrete operations: firstly the synthetic reproduction of the paranoiac’s way of seeing the world in a new light - with its rich harvest of unsuspected correspondences, analogies and patterns and secondly the compression of the these gaseous speculations to a critical point where they achieve the density of fact. But who is actually using this technique - is it the climate change deniers? The teen activists of Fridays for Future? The radical right-wing fear-mongers? Or the hysterical leftist hippies? Or all of us?

Gazing at the mutilated wood logs on the other hand, their hybrid all to human fragile and injured nature, we realize that it is time to leave these dichotomies behind and finally adopt a much more syncretic approach as Stacy Alaimo does in her 2014 publication ‘Bodily Natures’ where she proposes to follow an environmental ethics along the lines of trans-corporeality, meaning that human bodies and non-human natures are open to one another, always constituting each others environment and rendering the idea that we are alone in the universe nothing short of delusional; or very simply put: what we do to the environment, we ultimately do to ourselves.

Text by Laura Amann